As she went at it, his mother entered into a kind of ecstasy. The neighbors opened their shutters to listen in. Then the kicking would begin: “his head his stomach his chest.” When he doubled over into a fetal position to protect himself, she carefully unfolded him and proceeded. When he was young, she used to beat him savagely.

That is not the only ambivalence surrounding Ritwik’s mother.

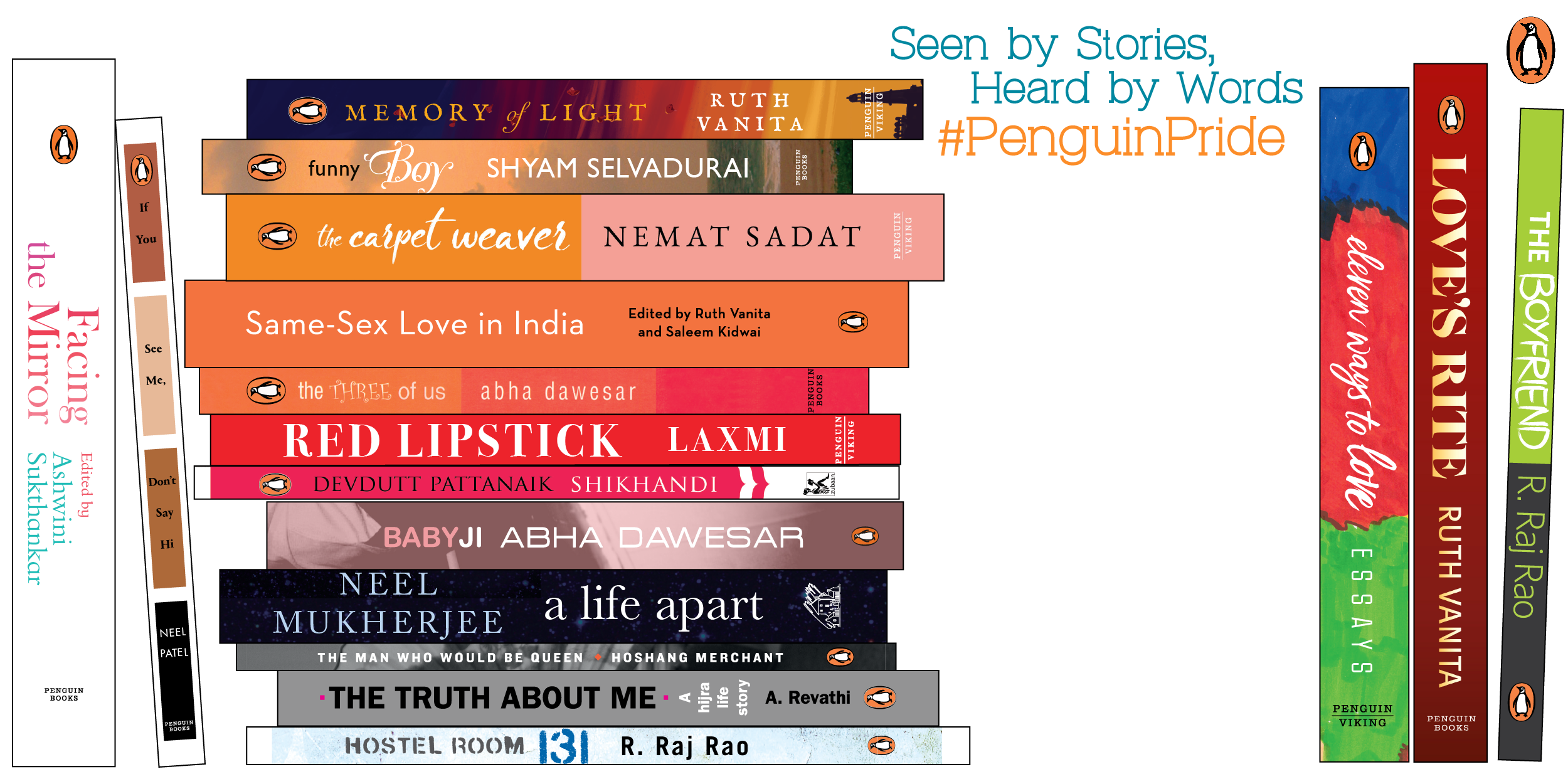

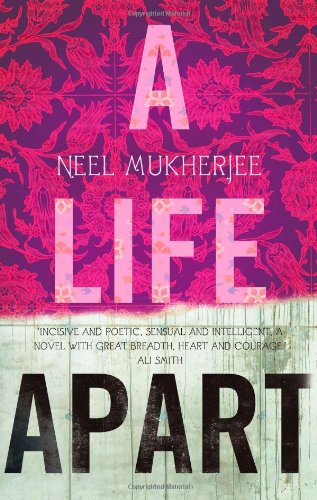

What is so unnerving here is the pull between grief and its opposites: disgust, comedy. and see if it really contained his mother’s rubbery navel and the stump of her umbilical cord.” Starving dogs hover at the shoreline, hoping to get a piece of flesh. On the way, he is “seized by an urge to root through the ashes and earth in the little bowl . . . (According to Mukherjee, there is a folk belief among Hindus that the navel is indestructible.) He must now go behind the crematorium, to the edge of the Ganges-a “dark slurry of putrefying matter”-and throw his mother’s remains in. An hour and a half later, Ritwik is handed an earthenware bowl containing, he is told, his mother’s navel. The stretcher is pushed down the rails and into the flames, and the doors slam shut. Her body lies on a stretcher alongside him, covered except for her lolling head. In fact, he is at the crematorium, waiting for a turn for his mother. On the first page of Neel Mukherjee’s “A Life Apart” (Norton), we see the hero, Ritwik Ghosh, standing in a line in South Calcutta, as if he were at the bank. Mukherjee’s novel is a powerful mixture of comedy, revulsion, and grief.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)